You wake up as a goat. You sprint into a gas station, headbutt a car, and watch it explode—sending your ragdoll body flying into the sky. Congratulations. You’ve just experienced the opening minutes of Goat Simulator, one of the most unapologetically absurd games ever made.

Video games have always been about immersion—but sometimes, that immersion means getting lost in a world where logic takes a coffee break. From hospitals treating “Lightheadedness” (where patients literally have lightbulbs for heads) in Two Point Hospital, to jellybean-shaped contestants faceplanting into spinning donuts in Fall Guys, to goats getting launched into space by licking jetpacks in Goat Simulator—the ways games make us laugh are as wild as they are wonderfully varied.

Unlike movies or books, video game humor is often participatory. You’re not just witnessing chaos—you’re actively causing it. Whether it’s flailing through obstacle courses in Fall Guys, shouting at your friends while burning soup in Overcooked, or watching your solemn hunter’s helmet clangs against every rung while sliding down a ladder in Bloodborne, gaming humor often comes from a blend of design, surprise, and player behavior.

In this article, I want to explore the many ways games make us laugh—from exaggerated physics and chaotic co-op modes, to writing that makes fun of the game itself, and even subtle comedy hiding in the most serious narratives. Using examples from games I’ve played and loved—from Fall guys to Two Point Hospital, from Cyberpunk 2077 to Death Stranding—this is a celebration of how humor sneaks, crashes, or dances its way into interactive worlds.

Absurd Worlds & Physical Comedy

Some games don’t even try to be serious—because making you laugh is the point. Goat Simulator, for instance, throws realism out the window within the first five seconds. You’re a goat. You can lick cars, launch into the stratosphere, and explode gas stations just by walking into them. The physics engine doesn’t obey the laws of nature—it obeys the laws of comedy.

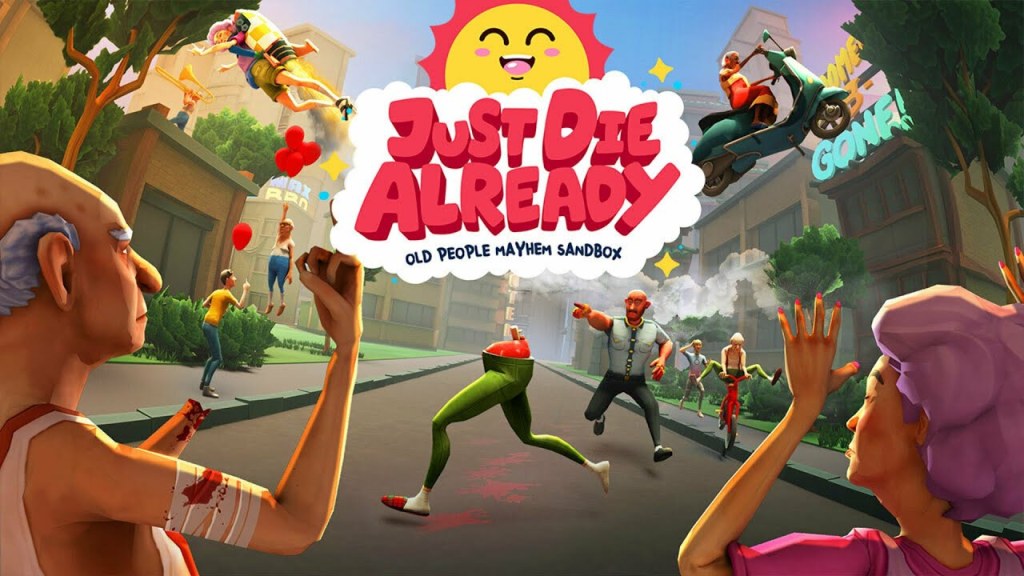

The same chaotic spirit runs through Just Die Already, where you play as elderly people rampaging through a city in search of freedom, mischief, and increasingly absurd ways to injure yourself. Whether it’s getting launched by a trampoline into oncoming traffic or losing a limb mid-flight, the slapstick violence is cartoonish and strangely cathartic. The game turns fragility into fuel for comedy—every misstep, fall, and explosion are part of the show.

Physical comedy in games works because it hands the player both the setup and the punchline. Take Human: Fall Flat, where you control a wobbly human who moves like a puppet held together with spaghetti. Simply trying to climb a wall can turn into a two-minute performance of failure and unintended parkour.

These moments don’t need dialogue. They don’t need story context. They’re funny because they’re visual, visceral, and just a little bit out of control. In absurd worlds with elastic physics, the player becomes part of the joke, whether they meant to or not.

Writing, Satire, and Fourth-Wall Breaking

Not all game humor is loud and chaotic—some of it is delivered with a straight face and a well-timed wink. Games like Two Point Hospital and Two Point Campus lean into parody with a distinctly British charm. On the surface, they’re management sims: you build hospitals, hire staff, and treat patients. But take a closer look at the diseases—like “Lightheadedness,” where patients literally have light bulbs for heads—and the illusion of seriousness quickly unravels. The games take professional settings and fill them with ridiculous premises, delivered so dryly that the deadpan delivery becomes part of the joke.

What truly seals the humor, though, is the game’s radio and announcement system. In Two Point Hospital, a radio host might cheerfully remind patients not to die in the aisle, or, when the building is engulfed in flames, calmly announce, “The hospital is on fire. What a great opportunity for simulated evacuation.”

This kind of humor lives in the background. It doesn’t break the flow of gameplay—instead, it creates a steady atmosphere of satire. It turns what should be stress (like a failing hospital) into entertainment, inviting you to laugh at the absurd bureaucracy and impossible expectations. The same tone carries over to Two Point Campus, where students take classes like “Knight School” and “Internet History,” all while the radio host casually complains about the smell of the dorms.

Some games break the fourth wall in quieter, more intimate ways. In Death Stranding, during moments of rest in the private room, protagonist Sam Porter Bridges stares directly into the camera—into your eyes—and makes subtle facial expressions in response to your actions. Tap the camera too much, and he might flick you off, splash water at you, or smirk knowingly, as if to say, “I see you there, player.” It’s an odd and slightly uncomfortable moment of mutual recognition between character and player, and it turns what could be a mundane rest area into a strange comedic ritual.

Even games that don’t center around humor sometimes slip in clever lines or meta references. Cyberpunk 2077 includes gravestones referencing John Wick, The Matrix, and other Keanu Reeves roles, poking fun at the fact that Johnny Silverhand looks suspiciously like, well… Keanu Reeves. Meanwhile, Metal Gear Solid V will slap a literal chicken hat on your head if you keep failing missions, making your badass super soldier look like an embarrassed toddler in a coop—and the game knows it.

This style of humor isn’t about slapstick or surprise. It’s about tone, irony, and a shared understanding between game and player. It’s the kind of comedy that says, “Yes, this world is ridiculous. We’re both in on it.”

Social Chaos & Player-Driven Humor

Some games don’t need a joke written into the script—just put a few players in a room with a goal, and the chaos will write itself. Goose Goose Duck, for instance, thrives on deception, miscommunication, and beautifully stupid accidents. In one match, a player was swallowed whole by a “Pelican”—a role that lets you eat other players and trap them in your belly. The twist? The swallowed player can still talk, loudly heckling the Pelican from the inside, distracting them mid-match. In an even wilder turn, another bad guy accidentally killed the Pelican, which “freed” the person inside—essentially performing an unintentional rescue by evisceration. They meant to help evil… and ended up doing a good deed.

Or take the time I was playing as a bomber duck, a role that lets you secretly pass around a ticking bomb. I tossed it to someone, who unknowingly passed it along to one of my own teammates—also a fellow bad guy. A few seconds later, boom: the bomb explodes, taking out my entire side. I lost, sure—but I was laughing too hard to care.

This kind of humor, born entirely from player behavior and unpredictable chain reactions, is at the heart of social chaos games. Overcooked does it with a kitchen instead of sabotage, where teammates yell over each other, set things on fire, and shove each other off ledges while trying to serve soup. One person forgets to chop onions, another throws a plate into the trash, and suddenly the whole kitchen is in flames. You’re technically cooperating—but it rarely feels like it.

In fact, the game is so notorious for sparking arguments that Chinese players gave it the nickname “分手厨房” (“breakup kitchen”). It’s the kind of game where laughter and shouting often overlap, and every level feels like a team-building exercise gone hilariously wrong.

Fall Guys, meanwhile, turns obstacle courses into slapstick arenas, where even if you play perfectly, someone else’s flailing jellybean body might knock you off a platform at the last second. There’s no coordination, no plan—just a swirling mess of chaos and color, where half the fun is watching others fall over.

The brilliance of these games is that they let players improvise comedy. The systems are flexible enough to allow for failure, betrayal, and unexpected outcomes—but structured enough to keep it all just barely under control. They don’t tell jokes; they set the stage and let players accidentally perform them.

Subtle Humor in Serious Narratives

Some games go out of their way to be ridiculous. Others prefer to keep a straight face—and that’s exactly what makes them funny. The Witcher 3 is a sprawling, dark, morally complex fantasy epic, with wars, monsters, and heartbreak around every corner. And yet, amidst all that gloom, there’s Geralt: stoic, grumpy, and perpetually done with everyone’s nonsense. He’s the perfect straight man in a world that refuses to let him rest.

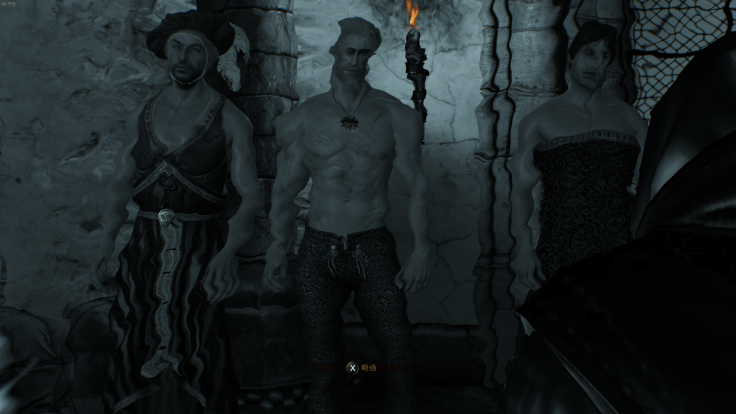

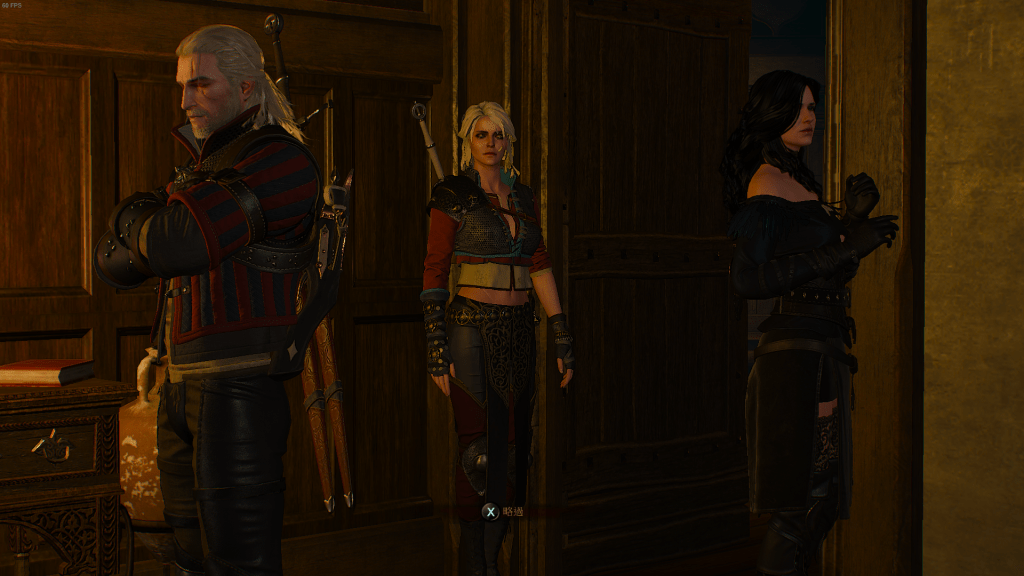

One moment he’s chasing down a child-snatching wraith; the next, he’s stuck helping an aristocrat find his favorite goat. He’s been forced into awkward dances, crammed into itchy doublets, and tasked with pretending to be someone’s date at a masquerade. In one famously hilarious scene, Geralt and two fellow witchers—normally gruff and battle-hardened—end up stumbling around drunk, donning women’s clothes and wigs in their mentor’s bedroom. It’s the kind of image that begs to be screenshotted, and one that feels all the more absurd because of how seriously everyone is taking it.

In a bit of brilliant meta-commentary, Geralt even questions the teleporting behavior of his horse Roach: “How’d you even get here? I didn’t leave you anywhere near this place.” The game knows it’s being silly—and it trusts you’ll notice.

This kind of humor works because it never breaks the world. Instead, it adds a layer of absurdity under the surface, letting the player discover it organically. Geralt’s deadpan reactions give you permission to laugh without shattering the immersion. The world is still dangerous. The monsters are still deadly. But sometimes, your grizzled antihero ends up wearing perfume to a party full of drunk nobles, or trying on women’s clothes after too much mead, and that’s just… life.

Red Dead Redemption 2 offers a similarly subtle—but often hilarious—form of humor. One of its most memorable moments comes during the quest A Quiet Time, where Arthur Morgan takes fellow gang member Lenny out for a drink. What starts as a calm evening quickly spirals into drunken chaos. As the world blurs and sways, Arthur stumbles through the saloon yelling “Lenny?!” at every stranger in sight—only to start seeing everyone’s face replaced with Lenny’s. It’s a brilliant bit of interactive absurdity, made even better by how seriously the characters are treating the situation, despite their utterly ridiculous state.

The game also leans into physical comedy through its highly detailed (and sometimes overly responsive) physics engine. You might trip over a rock while hunting a legendary animal, accidentally punch a stranger instead of greeting them, or get bucked into a tree because you brushed the wrong button while riding your horse. These moments aren’t scripted jokes—but that’s exactly what makes them funny. They emerge from the tension between the game’s heavy realism and your own clumsy humanity.

These moments remind us that humor in games doesn’t always need punchlines or pratfalls. Sometimes, it’s just the gentle absurdity of watching someone—or yourself—take something very seriously, and still ending up flat on their face.

Final Thoughts

Of course, not all humor in games comes from brilliant writing or clever design. Sometimes, it’s deeply local, meme-fueled, and completely untranslatable unless you were there. Two of my favorite examples are Summer in the Northeast and Chicken Hill, both small indie games that became viral sensations among Chinese players.

Summer in the Northeast is a chaotic, pixelated fever dream set in a rural village filled with exaggerated Northern Chinese stereotypes—from shirtless men dancing in the square to neighbors battling with shovels. The entire game feels like an inside joke pulled straight from Chinese social media, and the more you recognize the references, the funnier it gets.

Chicken Hill, on the other hand, is inspired by the viral meme phrase “鸡你太美” (“chicken you are so beautiful”)—a phonetic distortion of a performance clip by a Chinese idol. The game takes this joke and builds a surreal world out of it, complete with absurd sound effects, floating heads, and meme-heavy mechanics. It’s chaotic, ugly, and absolutely hilarious if you know the context.

But what really gives these games their punchline isn’t just the design—it’s the player culture surrounding them. The memes, reaction videos, live streams, and remixes that players create become part of the humor ecosystem. A game might be mildly funny on its own, but once it enters the chaotic hands of internet users, it transforms. Every TikTok parody, every sarcastic review, every Steam comment filled with emojis and slang—they all layer onto the joke, making the humor bigger than the game itself.

In that way, humor in games is never static. It evolves through participation. What starts as a visual gag or a clever mechanic can turn into a full-blown meme once it passes through the hands of players. Whether it’s Geralt in a wig, a bomb passed to the wrong person in Goose Goose Duck, or a shovel duel gone wrong in a pixelated village—half the joke lives outside the game, in the community’s retelling of it.

So in the end, games don’t need to be comedies to make us laugh. They just need to be honest enough to let the absurdity in—and generous enough to give players space to mess with it.

Leave a comment